The four painted panels in the huge fireplace surround in The Library at Combermere Abbey contain portraits from the late Sixteenth and early Seventeenth century. Each measures approximately 23 inches high by 18 inches wide. They show King Henry VIII, Queen Elizabeth I, and the man who re-built the Abbey as a country house after the dissolved Cistercian abbey had been granted to his father, Richard Cotton. But who is the subject of the fourth picture? Is it Richard’s father, Sir George Cotton? He died in 1545, when his son was five or six years old, and more than three decades before the date on the image of Richard. Could it be Richard’s son and heir, named George after his grandfather, who was only seventeen that year, but might well have grown a moustache in an attempt to look older, and more manly? At the youngest this man looks as if he is in his mid-twenties, and there’s little familial likeness. His great lace collar is of the period, as is the slashed black tunic showing the white (satin?) beneath. The portrait of Richard is dated 1579, and all the paintings appear to be contemporaneous, and were probably the work of the same artist.

For a long time the mystery image was said to be a portrait of James I, but he did not come to the throne until 1601 – though this portrait could have been added after that date – but crucially he is always depicted as bearded. Also, his beard was distinctive; long, wispy (“thin”, as contemporaries described it), and quite red.

The unmistakable likeness of Henry VIII, who brought the Cottons to power and wealth (detail)

The unmistakable likeness of Henry VIII, who brought the Cottons to power and wealth (detail)

Henry VIII’s second daughter, Elizabeth, Queen of England from 1558 – sixteen years after Combermere had been granted to Sir George Cotton (detail)

Henry VIII’s second daughter, Elizabeth, Queen of England from 1558 – sixteen years after Combermere had been granted to Sir George Cotton (detail)

Richard Cotton; born 1539 or 1540, died 1602 (one year after Elizabeth). The inscription in the top right of his portrait notes that he was 37 years of age at the time of the sitting (detail)

Richard Cotton; born 1539 or 1540, died 1602 (one year after Elizabeth). The inscription in the top right of his portrait notes that he was 37 years of age at the time of the sitting (detail)

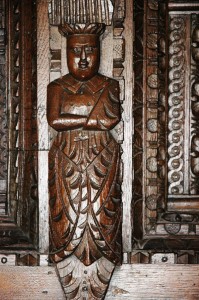

All we can say for sure is that he is an unknown Elizabethan gentleman (detail)

All we can say for sure is that he is an unknown Elizabethan gentleman (detail)

Conservator Harriet Owen Hughes took all four paintings to her studio in Liverpool for restoration. Quite apart from the work on the paint itself, a number of the backing panels on which the canvas had been stretched and glued had split, and these had to be carefully repaired. Now all four portraits are beautifully restored and have been returned to their rightful place in the fire surround.

Portrait of Henry VIII

Most portraits of King Henry VIII show him four-square, facing the viewer – though a small number depict him with his face slightly turned away, but with his eyes very definitely turned back to the viewer. His stare is always fearsomely direct, self-assured and uncompromising. Interestingly though, in the Combermere Abbey portrait his eyes are looking down slightly – not directly at the viewer.

Henry reigned for thirty eight years, and his appearance changed dramatically across those years; from lithe and highly active young man – fresh-faced and even gauche – to a bitter-looking, pig-eyed brute – always in great pain and suspicious of everyone. He had been dead more than thirty years when this work was undertaken. There would have been many sources of reference for the artist. The King has been depicted in middle age, at the height of his powers, rather than at the end of his life.

Our national image of Henry comes mostly from the portraits by Hans Holbein The Younger, who painted the King at least half a dozen times – the earliest being in around 1536 (not long after Holbein first came to England, with a letter of recommendation from Erasmus, addressed to Thomas Cromwell), and lastly in 1543 (unfinished as he died of the plague before it was completed). The Combermere portrait most resembles Holbein’s portrait of 1536/7, though the King looks rather more benign and less imperious. This shows Henry at around forty five years of age.

The contemporary portraits of Henry VIII which most resemble the Combermere portrait. In these and the Combermere portrait the king wears a similar hat, at an angle – down slightly on the King’s right hand sideHolbein’s portraits of the King were much copied, both as paintings and as engravings, and almost everyone would have seen one or more, and the King was instantly recognisable.

The Combermere portrait of Henry is 577 x 445 mm (606 x 470mm in frame), and is set in a plain wood ‘tray’ style frame. The painting is on three vertical oak boards, which are quite rough, and not camfered. The central board had a split running from the bottom, with canvas on the back. The left plank (as seen from the front) was split from the others, with an older repair in the top corner

There was incipient flaking along this break, some of old restoration. There was vehicular crackling and rough texturing throughout the background, which indicates overpaint, and the varnish was discoloured

In cleaning tests it became apparent that the background – which should be a brighter reddish colour – has been over-painted to cover pin-prick ‘crater’ losses probably caused by deteriorating lead salts in the dark areas. The inscription ‘(Henry) VIII’ shows through the over-paint above the head, and the original feathers in his hat are much bolder, though the black areas appear worn. The over-paint was readily soluble in acetone. There were some old woodworm holes in the wooden frame, so it was treated with Constrain to avoid future infestation.

Henry removed from his frame

Henry removed from his frame

The portrait in the press after gluing to close up the crack in the backing panel

The portrait in the press after gluing to close up the crack in the backing panel

As above, in a press

As above, in a press

Detail of Henry’s collar and beard before cleaning

Detail of Henry’s collar and beard before cleaning

King Henry VIII’s all-seeing left eye (and what things it saw!)

King Henry VIII’s all-seeing left eye (and what things it saw!)

Detail of trim on Henry’s hat, with first clean on the left

Detail of trim on Henry’s hat, with first clean on the left

During cleaning

During cleaning

During cleaning

During cleaning

First clean on Henry’s hat and forehead

First clean on Henry’s hat and forehead

First clean on the extreme left of the feather trim on his hat

First clean on the extreme left of the feather trim on his hat

As above; full frame with the first test clean on the left hand side of his hat

As above; full frame with the first test clean on the left hand side of his hat

Detail on Henry’s hat, just to the left of his ear, after the panels had been re-joined but before re-touching

Detail on Henry’s hat, just to the left of his ear, after the panels had been re-joined but before re-touching

Detail of the shoulder and edge of the collar, to the left, after cleaning

Detail of the shoulder and edge of the collar, to the left, after cleaning

Henry after cleaning and re-joining but before re-touching

Henry after cleaning and re-joining but before re-touching

Henry’s furrowed brow after cleaning

Henry’s furrowed brow after cleaning

The magnificent King Hal after cleaning, re-touching, and varnishing

The magnificent King Hal after cleaning, re-touching, and varnishing

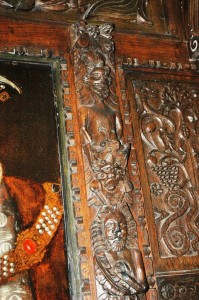

Portrait of Elizabeth I

The portrait of Elizabeth I measures 585.5 x 440 mm (with wood ‘frame’ – 605 x 470), and was found to have been painted on canvas. It was – in restoration-speak – marouflaged (a technique for affixing a painted canvas to a wall or similar surface, using an adhesive that hardens as it dries such as plaster or cement. to oak boards), un-champhered, with a canvas strip over the join, sitting in a plain wood ‘tray’ style frame with nails.

In initial cleaning tests there appeared to be a completely different ruff under the dark background to the one Elizabeth is wearing, and her hair has been added to. This means that the painting has been over-painted – and in the relatively recent past as this over-paint was readily soluble. It was not unknown for portraits of Elizabeth to be ‘modernised’ in the reign of Quenn Anne, but these alterations appear to be more recent, which is fascinating – though it is frustrating not to be able to date the changes.

All of the four portraits of Elizabeth I in a recent exhibition at The National Portrait Gallery were found to have changed in some way since they were first created. Advanced scientific techniques, such as paint sampling and infra-red reflectography, have helped us to unlock clues to their original appearance. Paint sampling on the most well-known of the four, the ‘Darnley’ portrait, has revealed that the now brown pattern on the queen’s dress would once have been crimson, and her extremely pale complexion would originally have been much rosier.

The latter indicates that the common assumption that Elizabeth had very pale features is largely a myth, true only for the later part of her reign when we know that she did wear pale makeup. X-ray examination of another of the featured portraits has revealed how an early seventeenth-century panel painting of Elizabeth was completely painted over in the eighteenth century to ‘prettify’ the queen in keeping with contemporary standards of beauty and style. Several other portraits of Elizabeth I exist that were similarly altered in the eighteenth century, indicating a posthumous revival of interest in her at this much later date.

Perhaps the most intriguing of the discoveries highlighted relates to a portrait that has very rarely been exhibited in the Gallery. This portrait of Elizabeth, created in the 1580s, has been painted over an unfinished portrait of an entirely different sitter!

The areas of the Combermere portrait which had not been over-painted were quite worn from earlier over-cleaning. The rough texture of some of the overpaint suggests the original paint may have been flaking. The painting was X-rayed, but disappointingly the alterations did not show. Since it was not possible to assess the condition of the original paint Hannah decided not to remove the over-painting.

First test clean test on the ruff ; left edge

First test clean test on the ruff ; left edge

Elizabeth I test clean with over-paint removed

Elizabeth I test clean with over-paint removed

Test clean with surface dirt only removed

Test clean with surface dirt only removed

A test clean on part of Elizabeth’s ruff

A test clean on part of Elizabeth’s ruff

The full portrait of Elizabeth I before any work had been undertaken

The full portrait of Elizabeth I before any work had been undertaken

Test cleaned but not re-touched

Test cleaned but not re-touched

Test cleaned and re-touched

Test cleaned and re-touched

A rather intimate and moving detail of Queen Elizabeth’s left eye after restoration

A rather intimate and moving detail of Queen Elizabeth’s left eye after restoration

A detail of her (second) ruff after restoration

A detail of her (second) ruff after restoration

Detail; nose and lips of a Tudor monarch

Detail; nose and lips of a Tudor monarch

A close-up of Elizabeth’s features after restoration

A close-up of Elizabeth’s features after restoration

The restored monarch in all her majesty

The restored monarch in all her majesty

The reverse of the portrait of Elizabeth I showing the split in the wooden panel

The reverse of the portrait of Elizabeth I showing the split in the wooden panel

This portrait is not a terrific likeness of the Queen, as we know her from portraits for which he sat. It is hard to say where the artist got his reference from. It could be said that he should have had an easier time which the Queen than with Henry VIII, as she was still on the throne and, of course, very recognisable. Perhaps familiarity bred contempt.

Her ruff is very modest by her own extravagant standards, and in all other paintings of her great emphasis is given to her clothing – which is not the case here. At the time the Combermere portrait was painted she was forty six years old.

Three broadly contemporary portraits of Elizabeth I, and one (bottom right) which is later. All with ruffs which are similar but less elaborate.Portrait of Richard Cotton

Richard Cotton was born in either 1539 or 1540, the eldest of six children born to Sir George Cotton and his wife, Mary Onsley. Richard was the fifth child and the only boy. He was probably named after his father’s brother, Sir Richard Cotton. The two brothers had emerged from obscurity in Wem in Shropshire, gone to London, and made their name at the court of King Henry VIII. George was knighted as an Esquire to The Body of King Henry, and soon after his son’s birth – in 1542 – he was granted the dissolved monastery of Combermere Abbey, together with its lands and income. This was mostly in recognition of Sit George’s service in running the household of the King’s illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset.

George died at the age of forty, in 1545, and it seems that little happened at Combermere for twenty years, apart from the demolition of almost all the Abbey buildings, and the collection of rents. In the early 1560s Richard set about building a country house for his family on part of the site of the Abbey – incorporating what had been The Abbot’s Lodgings as the house’s great hall. Richard’s portrait is dated 1579, so we can assume that the house was completed – or very close to completion – by that date.

Richard lived to be about sixty two, and was married three times. His first marriage, to Mary Mainwaring from Ightfield – close to Combermere – was when he was about twenty, and they had eight children in thirteen years. The first of these was George, who would inherit Combermere in 1602. George had two brothers, Arthur and Andrew. Mary died in 1578 and Richard married Jane Sulliard (or Seyliard). She died in 1596, having given Richard three more sons and a daughter. Finally he married Philippa Dormer, with whom he had two children – a son and a daughter.

The armorial shields seen on his portrait are very interesting. These are his stamp of identity; his statement of lineage and familial durability. To the left, dated 1579, is his crest of a falcon with its wings expanded. The two shields on the right of the portrait relate to the first two of Richard Cotton’s wives; Mary Mainwaring and Jane Sulliard. Both women obviously came from families prominent enough to have their own arms. At the time of the painting Mary had been dead for a year and Jane and Richard were newly married. Curiously, in the The Library at Combermere Abbey – what was The Abbot’s Lodgings – the arms of Mary and Philippa are displayed, but not those of Jane (though these date from the Nineteenth century).

The portrait measures 608 x 456 mm and is on oak, with a two breaks, one vertical and one slanting. The painting had split completely in two along the existing vertical break before it arrived in the studio. There was flaking along the breaks, some of old filling. There was also evidence of previous damage just to the right of the existing vertical break – a band of slightly discoloured retouching most noticeable in the face, and parallel damage from a corrosive liquid running down (which has also splashed on back). There was vehicular crackle throughout the background which may be over-paint. The varnish was moderately dis-coloured and readily soluble, except where there it has built up, which was mainly at the edges. The paint was in reasonable condition compared with the other paintings; did the artist take more care with the portrait of the man who was paying his account?

Richard Cotton before cleaning, showing the vertical crack in the oak panel The sleeve of Richard’s tunic during cleaning The reverse of the portrait showing the splitting Detail of Richard’s tunic, during cleaning The shoulder of the tunic during cleaning Detail of the portrait, after cleaning and re-joining but before re-touching After re-touching Before re-touching The top right of the picture (the ’37’ being Richard’s age at the time) after re-joining but before re-touching The full portrait after cleaning and joining but before re-touching

The full portrait after cleaning and joining but before re-touching

After cleaning and re-joining

After cleaning and re-joining

Detail after re-touching

Detail after re-touching

The full portrait after re-touching

The full portrait after re-touching

Portrait of George Cotton?

As discussed earlier, we do not know the identity of this gentleman, in the fourth panel, but the most likely candidate is definitely George Cotton, the son of Richard Cotton. As his heir, George would have been extraordinarily important in the dynastic landscape of a great Tudor gentleman like Richard. Richard was very proud of how far back his family stretched, and George was his familial investment in the future. It was no coincidence that he was named after Richard’s father. There may be further evidence in the fact that the two great Tudor monarchs were placed centrally, flanked by the ever-loyal Cotton gentlemen.

Born in 1560, George lived to be eighty seven years old – a very good age. His wife, Mary Bromley of Shifnal in Shropshire, was born nine years later, and she died in the same year as her husband, aged seventy eight.

Richard made a good marriage in wedding Mary. She was the daughter of Sir George Bromley, who was a very great man in the county and a significant figure nationally. Born in 1526, he was a lawyer, landowner, politician and judge, as well as being – at different times – the MP for Liskeard in Cornwall, Much Wenlock, and Shropshire. He was an important member of The Council of the Marches. He died in 1589 and was buried beneath a splendid tomb erected by his son, in Saint Peter’s church in Worfield. By this time the Cottons of Combermere were very grand in their own right, but being Sir George Bromley’s son-in-law would have done George no harm at all.

George and Mary had eight children together, between 1588 and 1609. The first seven must have caused George some worry as they were all girls. He must have watched the procession with concern for the want of an heir, but the last pregnancy gave him just that; Thomas, who was thirty eight in the year that he inherited the Combermere estate, after Richard died in Stoke, near Coventry, in Warwickshire, in 1647.

The portrait measures 605 x 512 mm. The painting is on canvas, lined, on a fixed strainer which is bowed. The original tacking edges have not been cut.

There was a small hole in both cavasses near the bottom left, and there was an all-over raised crackle with some old paint losses at intersections and larger losses near the bottom edge.

The most recent varnish is thick and very shiney, emphasising the texture of the crackle; an older, discoloured, varnish has been removed from the tops of the crackle but left in the hollows. The older varnish appears fairly resistant to solvents; the most recent is soluble. The condition of the paint where test areas were cleaned had widespread small damages.

Before restoration, with a cleaning test undertaken on the chin

Before restoration, with a cleaning test undertaken on the chin

A detail of the fine lace ruff during cleaning

A detail of the fine lace ruff during cleaning

The left hand side of the lips and jaw, during cleaning

The left hand side of the lips and jaw, during cleaning

The ruff during cleaning

The ruff during cleaning

A small area of damage; to be filled and re-touched

A small area of damage; to be filled and re-touched

After cleaning and repairing but before re-touching

After cleaning and repairing but before re-touching

The face in close up, after treatment

The face in close up, after treatment

The full portrait, restored The four portraits back in place in the fire surround in The Library

We are hugely grateful to conservator Harriet Owen Hughes for her very important work on these historic portraits, and for her comprehensive recording of the undertaking. You can click here for Harriet’s details on the Institute of Conservation’s register, including her contact details.

Our thanks also go to heraldry expert Peter Marshall for his advice regarded the heraldic devices.

The restoration of the portraits was supported by The Heritage Conservation Trust (which is supported by the HHA). The Heritage Conservation Trust is an independent charity set up in 1990 on the initiative of historic house owners to provide support for historic properties.

The HCT supports the conservation of works of art at historic houses open to the public as well as education, access and research initiatives in and about these special places. Within the last year the HCT has expanded its activities to support access and educational initiatives in historic houses and gardens and to help research projects linked to the conservation of the historic or artistic contents of houses, alongside its continuing work to assist restoration of works of art.

Combermere Abbey is very grateful to the HCT for its invaluable assistance in the restoration of these fascinating and historically very valuable portraits. Click here for more details about the Trust.