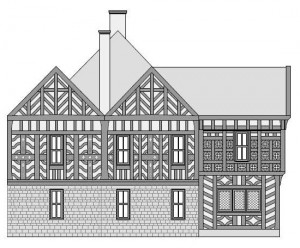

The fireplace surround in The Library at Combermere Abbey is a magnificent piece of Tudor carpentry, dating from the 1560s, when Richard Cotton – son of Sir George Cotton, to whom the estate was granted after the Dissolution – built the large timber-framed house.

The fireplace surround in The Library at Combermere Abbey is a magnificent piece of Tudor carpentry, dating from the 1560s, when Richard Cotton – son of Sir George Cotton, to whom the estate was granted after the Dissolution – built the large timber-framed house.

The surround measures around fourteen feet square, and it is a composite of dozens of individual elements, of all sizes, pinned together to create a unified whole. Much of the decoration was carved, but not as much as one might at first think.

The decoration is typical of its period, but is not hugely sophisticated, and may have been the work of a local craftsman. The tall columns to the extreme left and right, and several other details, show Italianate influence and more than hint at the Renaissance. Reference for this sort of work would not have been difficult to come by at this point. On the other hand, there are primitive and possibly mythological elements, and images of Native North American Indians. The English exploration of the eastern seaboard of what is now the USA began with Cabot at the end of the Fifteenth century, but really got underway with Elizabeth I’s skilled and intrepid ‘sea dogs’ from about 1560 – though the main thrust of exploration came after the defeat of the Spanish fleet in 1588. There was huge interest in the voyages of discovery, and images of North North American were widely distributed in England. Their presence on the fireplace surround might hint at a later date.

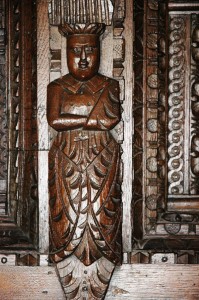

Depiction of a Native North American Indian

Depiction of a Native North American Indian

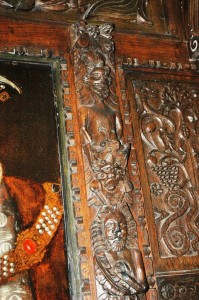

This female ‘savage’ may also a North American Indian, though she could possibly be negroid. Curiously her nipples point forwards in parallel, though her modesty is preserved by a cartouche. Her upstretched arms end in paw-like hands, merging into exotic foliage

This female ‘savage’ may also a North American Indian, though she could possibly be negroid. Curiously her nipples point forwards in parallel, though her modesty is preserved by a cartouche. Her upstretched arms end in paw-like hands, merging into exotic foliage

This panel is fascinating; it is unlike anything else in the ornamentation. Monsters are depicted devouring their own tails, and the style is Anglo-Saxon and pagan. The motif is common, and is considered to represent immortality (borne of the serpent or snake shedding its skin and renewing itself). It is hard to see where the inspiration for this came from and why it was included.

This panel is fascinating; it is unlike anything else in the ornamentation. Monsters are depicted devouring their own tails, and the style is Anglo-Saxon and pagan. The motif is common, and is considered to represent immortality (borne of the serpent or snake shedding its skin and renewing itself). It is hard to see where the inspiration for this came from and why it was included.

These bare-chested and bearded males may also represent savages, though facial they do look European. The artist’s knowledge of foreign physiognmy was doubtless less than exact.

These bare-chested and bearded males may also represent savages, though facial they do look European. The artist’s knowledge of foreign physiognmy was doubtless less than exact.

The head-dress is made up of exotic foliage resembling a coconut tree. This exotic decoration may just be a reflection of current interest in all things relating to foreign exploration, or it may be an implication that although the Abbey is situated deep in the English countryside, its owner is sophisticated and internationalist.

This figure appears to be European but seems to be wearing a robe over his left shoulder. With his long hair and beard he bears a surprising resemblance to the author of this website.

The head-dress is made up of exotic foliage resembling a coconut tree. This exotic decoration may just be a reflection of current interest in all things relating to foreign exploration, or it may be an implication that although the Abbey is situated deep in the English countryside, its owner is sophisticated and internationalist.

This figure appears to be European but seems to be wearing a robe over his left shoulder. With his long hair and beard he bears a surprising resemblance to the author of this website.

This figure, bare-chested again and wearing a simple piece of fabric over one shoulder and across his groin, surmounts a semi-abstract face – from the mouth of which appears foliage and – what? – two avocado pears?

A stylised face of – perhaps – a wolf, above what may be more exotic fruit.

A great claw, which forms the base of a column but does not relate to any other sculptural element. By way of contrast to almost everything else, a crude carving of a bearded face, surrounded what appear to be rays of the sun. Similarly heads, with dour expressions, appear in both Anglo-Saxon and Celtic art – particularly stone carvings.

By way of contrast to almost everything else, a crude carving of a bearded face, surrounded what appear to be rays of the sun. Similarly heads, with dour expressions, appear in both Anglo-Saxon and Celtic art – particularly stone carvings.

This panel with its Romanesque arch is intricately carved with foliage. The exposed pin heads show how the different components have been amalgamated to create the finished piece.

This panel with its Romanesque arch is intricately carved with foliage. The exposed pin heads show how the different components have been amalgamated to create the finished piece.