The restoration of the ceiling in The Library at Combermere Abbey was undertaken by Hare & Humphreys, a Royal Warrant-holding company based in London. Founded in 1987, the firm has a hugely distinguished list of clients. Peter Hare, was born in Scotland, but when he was young his newly-widowed mother moved to rural Norfolk, which is where he was raised. In contrast, Paul Humphreys was brought up in suburban east London. Peter’s early interest was interior decoration, while Paul worked for a company which specialised in cleaning and restoring historic churches.

They first met in 1978 when they were recruited to work on the re-instatement of The William Morris room at the Victoria & Albert Museum. Inspired by Morris’s Arts and Crafts movement, they realised that they both had “the most extraordinary desire and drive to revive the seemingly lost respect for decorators, conservators and artists alike, by creating a modern 20th century company with the spirit, ideals and commitment shown a century earlier”.

Peter Hare formed his first company in 1981 and Paul worked alongside him on many commissions. This work took them to many corners of the world, and their clients were interior designers, billionaires (mega-yachts were part of their portfolio), kings, sultans, and rock stars. In the UK they undertook conservation in the National Gallery, the Palace of Westminster, and both Houses of Parliament.

The new company of Hare & Humphreys was created around the restoration and re-decorating of the Spencer family’s original London home, Spencer House in Saint James’s – built between 1756 and 1766, and one of the most extravagant aristocratic town houses in London. It was commissioned by the first Earl Spencer – a direct ancestor of the late Diana, Princess of Wales.

A detail of a ceiling at Spencer House, conserved by Hare & Humphreys

A detail of a ceiling at Spencer House, conserved by Hare & Humphreys

Five years later they were called to Windsor in the wake of the catastrophic fire at Windsor Castle. Their first task was to assess the extent of the damage and create a plan for the re-building and restoration. The firm’s work on – in particular – the Crimson Drawing room, the Green Dining room, St George’s Hall, and the State Dining Room was acknowledged as being world-class, and resulted in Her Majesty the Queen awarded the company her Royal Warrant.

Hare & Humphreys’ Royal Warrant for their work on Windsor Castle

Hare & Humphreys’ Royal Warrant for their work on Windsor Castle

Since then the firm has worked on many of the most important and prestigious conservation projects imaginable, including Saint Paul’s Cathedral, Hampton Court Palace, Dover Castle, the Royal Academy’s base at Burlington House in Piccadilly, the Monument to The Great Fire of London, and The Howard Theatre at Downing College in Cambridge University. Their work covers every style and age of building, be it private, academic, public, or ecclesiastical. The firm’s range of work runs from consultancy and design, right through to undertaking every aspect of conservation, no matter the number of disciplines involved. As well as the structure of a building and any form of decorative surface, Hare & Humphreys will restore furniture and internal fittings.

Saint Paul’s Cathedral, London

Saint Paul’s Cathedral, London

As Hare and Humphreys say, “We believe that the care of historic interiors is a specialised discipline, requiring detailed knowledge of all the elements of the interior, as well as the materials and the techniques involved in making and restoring them. The scheme to be conserved could comprise many different materials, such as paint, timber, stone, plaster, gilding, and upholstery. It also involves a multitude of specialist trades including decorating, fine art, french polishing, joinery, fibrous plastering, and many others”.

In 2012 the firm completed one of their most exciting and original commissions. A new Royal barge – the first built for 250 years – was built for Queen Elizabeth II’s sixtieth jubilee celebrations, and Hare & Humphreys was asked to paint and gild the vessel.

Gloriana was to be at the very centre of the flotilla of the Thames Pageant, carrying the Royal Family. Detailed consultation with the Royal Household and the College of Arms was needed to ensure that protocol was not breached in any particular. The decoration was designed to reflect the tradition of historic Royal barges, whilst also incorporating references to the Queen’s six decades as monarch. Tributes were added in recognition of the long marriage to, and great support from His Royal Highness The Duke of Edinburgh. These took the form of the emblems of the Lord High Admiral which can be seen painted either side of the rear cabin entrance.

The external gilding on Gloriana used fifteen hundred books of 23.5 carat gold leaf. A trompe l’oeil panelled ceiling of the Royal cabin was inspired by the birds which can be seen on the Thames, from the river’s source to the estuary – the crests of all the Thames-side boroughs were represented within this scheme. The design also included images showing other royal barges from centuries gone by, and as if it wasn’t enough to have painted the barge itself, Hare & Humphreys’ craftsmen hand–painted the boat’s eighteen oars and the large rear rudder with depictions of legendary sea serpents.

So far as the work needed on The Library at Combermere Abbey was concerned, Helen Hughes, the specialist conservator who had conducted a detailed survey of The Library, suggested three firms to the Abbey’s owner, Sarah Callander Beckett. They were invited to visit the Abbey and tender for the work accordingly. Two of those companies submitted similar prices, but Sarah was very impressed by Hare & Humphreys’ approach and in particular by the firm’s staff.

The head of their team was Cathy Littlejohn, H&H’s Conservation & Projects Director, and Sarah says that she was not only impressed by her obvious knowledge, but also by her enthusiasm to undertake the conservation work at the Abbey. As Sarah says, “Quite apart from the team’s abilities, I was going to be having all these people more or less living in my family house for a few months, so it was a great help that I liked them”.

Cathy’s first visit was in September 2013, and it was agreed that work should begin in early March 2014. The conservators who were on site full time were to be accommodated during the working week in some of the Abbey’s self-catering holiday cottages.

Cathy Littlejohn says that right from the beginning she realised that it would be a very interesting project. “I could see the quality of the ceiling immediately on my first visit – and its faded glory. I went up into the roof space above the ceiling and was amazed by the history encapsulated in just that relatively small area. I also remember it being cold and overcast, and, to be honest, the room was rather forbidding. You do find though that once you get underway on a job you warm to any room, as it reveals its secrets to you.

“I was very confident that we could do The Library justice, and I also knew that it would be a very satisfying job to undertake. No job is ever routine for us. There are always things which we don’t expect. We were removing years of dirt, just caused by the passing of time, and it was a wonderful transformation. I find that you look back at the first photographs you took, after a few weeks, and have forgotten just what a difference you have made.

“At the Abbey we encountered no major problems, just difficulties which had to be addressed along the way. One of our biggest problems had nothing to do with the ceiling at all; we had a bad batch of paint stripper sent to us, which was too runny to use. That aside, we had to address the black mould we found, and some of the surfaces weren’t what he had expected. The small triangular panels of painted decoration turned out to be on either canvas or paper, and they needed treating differently. We had expected to clean the dais but up close we saw that the darkening wasn’t actually dirt but an antiquing effect which had been applied!

Two of the triangular motifs; on the bench being cleaned and restored, and re-instated

“Within The Library we were faced with many different surfaces – the painted crests, the wooden shields, paper and canvas as well as plaster – and they all needed different approaches so far as their conservation was concerned.

“Each of the decorated panels was unique. There was no standardisation, so we couldn’t use a template, and each one had to be treated individually. Like so many old buildings The Library is incredibly idiosyncratic. For example, the rising and falling profile of the cornice is wonderful. You could only really see that fully when you got up on scaffolding and looked along it.”

One of the heraldic shields before and after conservation

Something which the Abbey staff realised and appreciated about Hare & Humphreys’ team was the knowledge and experience at all levels. The firm puts their operating teams together very carefully, making sure that within each team they have the expertise in total to tackle any eventuality. Some of the firm’s staff have specialist university training, but others come up through the trade and then move into heritage restoration and gain experience on the job. Cathy says, “We are very positive about both routes, and working on castles, palaces and many of the greatest and most historic buildings in the country means they have enormous practical experience. The crafts people learn from the graduates and vice versa.”

It’s also true to say that the team really enjoyed working at Combermere. Their enthusiasm for the job, and the pleasure they derived from it, were manifest – but they also enjoyed staying in the Abbey cottages – and dining nightly up the lane at The Combermere Arms.

The conservation work was undoubtedly timely; as Cathy says, “The flaking of the paint would have continued, and in fact probably accelerated, so that if the job had been postponed for, say, five years there would have been far less to work with. Also the plasterwork was decaying worryingly. We had to pin back quite a lot of plaster on both the panelling and the beams. Some of the smaller motifs on the cornicing had fallen away, and that would have continued – and further loos of those would have been a real shame. Thinking ahead by five years again, you would certainly have seen a real deterioration. It’s a very good thing that the problems were addressed when they were.”

The coving on the north wall of The Library, with painted shields, before and after conservation by Hare & Humphreys

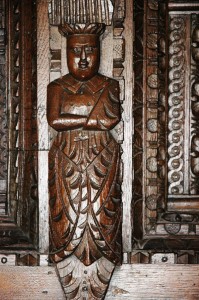

The fireplace surround in The Library at Combermere Abbey is a magnificent piece of Tudor carpentry, dating from the 1560s, when Richard Cotton – son of Sir George Cotton, to whom the estate was granted after the Dissolution – built the large timber-framed house.

The fireplace surround in The Library at Combermere Abbey is a magnificent piece of Tudor carpentry, dating from the 1560s, when Richard Cotton – son of Sir George Cotton, to whom the estate was granted after the Dissolution – built the large timber-framed house. Depiction of a Native North American Indian

Depiction of a Native North American Indian

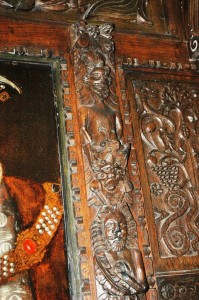

This female ‘savage’ may also a North American Indian, though she could possibly be negroid. Curiously her nipples point forwards in parallel, though her modesty is preserved by a cartouche. Her upstretched arms end in paw-like hands, merging into exotic foliage

This female ‘savage’ may also a North American Indian, though she could possibly be negroid. Curiously her nipples point forwards in parallel, though her modesty is preserved by a cartouche. Her upstretched arms end in paw-like hands, merging into exotic foliage

This panel is fascinating; it is unlike anything else in the ornamentation. Monsters are depicted devouring their own tails, and the style is Anglo-Saxon and pagan. The motif is common, and is considered to represent immortality (borne of the serpent or snake shedding its skin and renewing itself). It is hard to see where the inspiration for this came from and why it was included.

This panel is fascinating; it is unlike anything else in the ornamentation. Monsters are depicted devouring their own tails, and the style is Anglo-Saxon and pagan. The motif is common, and is considered to represent immortality (borne of the serpent or snake shedding its skin and renewing itself). It is hard to see where the inspiration for this came from and why it was included.

These bare-chested and bearded males may also represent savages, though facial they do look European. The artist’s knowledge of foreign physiognmy was doubtless less than exact.

These bare-chested and bearded males may also represent savages, though facial they do look European. The artist’s knowledge of foreign physiognmy was doubtless less than exact.

The head-dress is made up of exotic foliage resembling a coconut tree. This exotic decoration may just be a reflection of current interest in all things relating to foreign exploration, or it may be an implication that although the Abbey is situated deep in the English countryside, its owner is sophisticated and internationalist.

This figure appears to be European but seems to be wearing a robe over his left shoulder. With his long hair and beard he bears a surprising resemblance to the author of this website.

The head-dress is made up of exotic foliage resembling a coconut tree. This exotic decoration may just be a reflection of current interest in all things relating to foreign exploration, or it may be an implication that although the Abbey is situated deep in the English countryside, its owner is sophisticated and internationalist.

This figure appears to be European but seems to be wearing a robe over his left shoulder. With his long hair and beard he bears a surprising resemblance to the author of this website.

By way of contrast to almost everything else, a crude carving of a bearded face, surrounded what appear to be rays of the sun. Similarly heads, with dour expressions, appear in both Anglo-Saxon and Celtic art – particularly stone carvings.

By way of contrast to almost everything else, a crude carving of a bearded face, surrounded what appear to be rays of the sun. Similarly heads, with dour expressions, appear in both Anglo-Saxon and Celtic art – particularly stone carvings.

This panel with its Romanesque arch is intricately carved with foliage. The exposed pin heads show how the different components have been amalgamated to create the finished piece.

This panel with its Romanesque arch is intricately carved with foliage. The exposed pin heads show how the different components have been amalgamated to create the finished piece.