Kathryn Callander has just finished her fourth year studying Architecture at Tulane University in New Orleans. Her family is from San Francisco and she is a cousin of the owner of Combermere Abbey, Sarah Callander Beckett. On a recent stay at the Abbey Kathryn surveyed the timber structure of the Abbey from the inside of the building, taking a large number of measurements and feeding those dimensions into a CAD programme. With that data in place she was able to create an image of exactly how the Abbey looked when it was re-built as a private house by Richard Cotton in the 1560s, while Queen Elizabeth I sat on the throne of England.

Combermere Abbey had been a Cistercian house since 1133, and in 1539 it was seized by Thomas Cromwell’s agents under authority granted by Henry VIII. The last Abbot, John Massey, surrendered the building and all its lands, and in 1542 the entirety was granted to Richard’s father, Sir George Cotton, who was comptroller of the household of King Henry’s illegitimate son, Henry Fitzroy, Duke of Richmond and Somerset.

Sir George and his brother Sir Richard Cotton were the sons of John Cotton and Cecily Mainwaring, who lived at Alkington – south of Whitchurch in northern Shropshire, and only a few miles from the Abbey. The two brothers came from a modest background in a part of the kingdom far from London and the court, but became hugely successful courtiers. Both men were knighted by Henry, and both were granted great estates (Sir Richard’s was in Hampshire).

It may be that Sir George lobbied to gain Combermere Abbey and its lands out of affection for the area where he was brought up. Certainly he would have known the Abbey and its lands well. He might have enjoyed the ‘Local boy makes good’ element. During his lifetime (he died young, in 1545, aged 40) he would certainly have collected the income from the estate, but his early death left the creation of a new house to his son – though demolition and the sale of materials not required for re-use may well have started earlier.

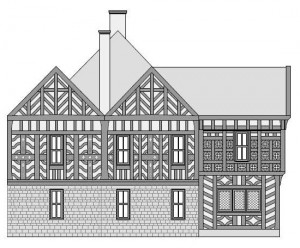

The west front of the Tudor house.

The west front of the Tudor house.

The Abbey church, its cloisters and almost all the ancillary buildings were demolished, and all evidence of their original positions was erased. The building materials were doubtless used elsewhere – probably sold off – and only a small amount was needed for the re-building – mostly timber and sandstone. Almost all that was kept of the Abbey’s structure was the high status central section around The Abbot’s Lodgings, which was in the style of a manorial great hall, with the main room on the first floor, and a relatively newly-built chimney on the east wall.

The stone-built ground floor seems to have been kept intact, and new wings were added to the north and the south. The building was symmetrical, with five identical gables (save for a quattrefoil in the centre) but the roof line dips sharply to the north (see below). The chimneys are assymetrical. The lantern in the centre of the roof was a Tudor addition, used by spectators to watch hunting of all and any kind on the land surrounding the Abbey. The gabled wings to the north and south projected forward to create a C-shaped plan.

Kathryn’s survey accords exactly with the 1730 drawing of the Abbey. This is very useful; having established that the depiction of the Abbey itself is valid we can put our faith in the other buildings and both the gardens and landscape. The west front of Combermere Abbey, drawn almost 200 years after the re-building.

The west front of Combermere Abbey, drawn almost 200 years after the re-building.

It is possible that the further wing and other buildings to the south of the Abbey’s core were also built in Tudor times, given their architectural style, though possibly shortly after the main was block was completed. The much lower status range to the north west, separate from the house and probably not used as accommodation, was demolished at some point. Where this building stood is now part of the lake (the two meres were joined later to create a single 150-acre lake).

The north face of the Abbey and the return of that face.

These elevations show that at the northern end there were two gables and a valley in the roof. Again the stone ground floor has been retained from the pre-Dissolution structure (though possibly re-worked to some degree), but the projecting wings are entirely timber-framed.

We are very grateful to Kathryn for her work, and wish her well for the future.