In 1919 Combermere Abbey was acquired by Sir Kenneth Crossley; the only time in the estate’s history that it has been sold, and only the second time it had changed ownership.

Sir Kenneth, a Manchester industrialist, did what all Englishmen so when they made their fortune – he bought a large and historic country estate. He had previously lived at Mobberley Hall, not far from his factories – and owned a retreat called Pullwoods built by his father on the north west side of Windermere, just south of Ambleside. He decided to bring up his family at Combermere (having previously considered Vale Royal Abbey just south of Northwich) Pullwoods, which was orginally modelled on Bramhall Hall in north east Cheshire, was sold in 1935.

Pullwood in Cumbria as it is today – exactly as it looked when Sir William built it. It is now holiday apartments (now known as Pull Woods).It’s not entirely accurate to call Kenneth self-made. He took the fortune made by his father and didn’t blow it all, as the second generation often does, but consolidated it and increased it. And he did this by building cars very early in the Twentieth century, and then diversifying into charabancs, lorries, vans, tractors – and staff cars, tenders, military-spec tractors, ambulances, armoured cars, and planes for the RAF.

Kenneth Irwin Crossley was born in 1877, the son of William Crossley. Ten years earlier, William (born 1844) and his elder brother Francis (always known as Frank), had bought a small engineering company based at Great Marlborough Street in Manchester; John M Dunlop. The brothers were from Northern Ireland, and had both served apprenticeships in engineering; Frank was more the engineer, and William the businessman. The firm made pumps, presses and small steam engines. The name was changed to Crossley Brothers and Dunlop. The firm grew rapidly, and after just four years they moved to larger premises in Openshaw, east of Manchester.

Sir William Crossley; from his obituary in the Manchester Evening News, 1911

Sir William Crossley; from his obituary in the Manchester Evening News, 1911

As early as 1869 they had acquired the rights – for the whole world except Germany – to Otto and Langden’s gas-fuelled atmospheric internal combustion engine, and just before they bought John Dunlop’s business they broadened that agreement to include the German engineers’ four-stroke engine. The Crossleys pounced on every advance they saw; hot tube ignition, carburettors, and the Diesel engine – and bought the rights. A year after the start of the Twentieth century their engines were being built into road vehicles, and from 1905, in Leyland buses.

Kenneth joined the company, now called Crossley Engineering, and by 1904 was working on their first car. What was more natural than for a company which built engines to start building cars, as their popularity was taking off? (Well, some did and some didn’t; the great Wolverhampton engine makes Villiers decided to remain specialists. They made motors for cars and bikes and supplied engines to their Sunbeam division, but kept the engine facility at arm’s length, supplying dozens of other companies, which they could not have done if they were rivals.)

Sir Kenneth Crossley with his youngest daughter, Pamela; born 1913Crossley Motors was created as a new company in 1906, which was indicative of the faith they had in the new project, and it that year they showed their first car at the motor show. The links with German engineers remained strong; Kenneth was very impressed by early Mercedes Benzes and he aimed to match their quality, and like them, go for the top of the market. Crossley Engineering had pioneered assembly line construction techniques, and they inspired Henry Ford – who visited the Manchester factory before he set up his factory. Where he saw mass appeal for his cars though, the Crossleys, perhaps given their fine engineering background, either decided to go into the market at a higher level of quality, or simply didn’t see the possibilities for a mass market.

The first Crossley car was a large open tourer with seats for four, powered by a four-cylinder engine producing 22 horsepower (soon uprated to 40), with lightweight pistons, an automatic carb, internally-expanding brakes, and chain final drive. The contacts with Henry Ford obviously continued; he bought one of the early Crossley car engines and had it installed in one of his Model Ts. In 1906 secondary shaft drive was introduced, though chain drive was still an option. Their marketing slogan was that Crossleys had “The good points of every car and the bad points of none”. Not snappy but made more sense than “Durch Sprung Technik”.

By 1909 the company was well-established and respected. The cars were stylish and well made, as was reflected in the price; ££500 for a rolling chassis, £800 complete (at a time when a skilled worker could expect to earn £3 a week). In that year new designs were introduced, including smaller, less expensive sporty models, four wheel braking was standard, and the gearbox was mated to the engine in a single, unified block – albeit with the cylinders grouped in two pairs.

William and Frank Crossley were devout Christians. They used the Coptic cross as the company emblem on their cars, and refused to sell vehicles to customers whose business they disapproved of. Being teetotallers they would not sell lorries and vans to breweries.

In 1912 Crossley started making commercial vehicles, and with the coming of World War One they were perfectly placed to provide a range of vehicles to the British military, and the factory went over completely to wartime production.

The core vehicle was to be the Crossley 20/25 – albeit with a number of body variants, and designed ‘WO’ for War Office by Crossley (and, perversely ‘Model J’ by the War Office). In civilian trim it was 162 inches long and 63 inches wide, with a track of 54 inches and a wheelbase of 126 inches, so it was a good-sized car and could seat six with only a slight squeeze. It was powered by a 4,531 cc engine, which gave it a top speed of 55 mph. Crossley had produced just over two thousand for the road before August 1914, and went on to supply at least six thousand to the government (and possibly many more; some sources say ten thousand), having quickly stepped up output. Unfortunately no reliable figures survive for military production, or how many were made in the various body types.

Military specification Crossley 20/25s lined up for despatch from the factory

Military specification Crossley 20/25s lined up for despatch from the factory

A Crossley in military ambulance trim

A Crossley in military ambulance trim

An officer with an ADC and a driver in a Crossley outside Windsor Castle

An officer with an ADC and a driver in a Crossley outside Windsor Castle

The 20/25 proved very versatile and was more than up to the job. As staff cars they looked a lot like civilian cars, but obviously without any unnecessary adornment or glitz, and painted in military drab. Almost all models had twin rear wheels, bolted together, and the spare wheels mounted on the running board on the driver’s side were always doubled up. Some photos show Crossley staff cars with full-width disc wheel covers, which were not standard.

A simple rear superstructure with three hooped ribs under a canvas top made the 20/25 into a light lorry. A fully-panelled solid rear made of plywood, mahogany, ash wood and fabric, created a full-sized ambulance, a mobile workshop, or – for the Royal Flying Corps – a light tender, known as Standard Light Transport. These models had a lower rear axle ratio than the staff cars, though an RFC tender tested by the War Office at Brooklands was found to be capable of 50 mph – and with a full load. The tender could accommodate eleven men seated, and the ambulance had room for four stretchers, one above the other on either side.

Two young First World War officers with their Crossley staff car A Crossley used as a tender for the Royal Flying Corps; the precursor of The RAF

A Crossley used as a tender for the Royal Flying Corps; the precursor of The RAF

Military specification 20/25s were despatched to almost all the major theatres of war; Mesopotamia, Africa, Salonica, Russia, Egypt, and India – as well as France and Belgium.

In 1917 the engine power was increased, being designated as the ‘X type’. In the same year two 20/25 were delivered to the BEKOS factories in Russia, as part of an agreement for the Russians to manufacture the model under license. Hardly had Cecil Bianchi, one of Crossley’s most senior employees, arrived with the vehicles than the Bolshevik revolution erupted and he and his colleagues had to flee for their lives.

It is no surprise that such an enthusiastic automotive pioneer as Kenneth should take to powered flight with a passion too. In August 1913 he was a guest of Mr Herbert Stanley Adams at Windermere, who had been the first person in the British Empire to take off and land on water, and flew in his flying boat, ‘Waterhen’ (built at Windermere by Captain Wakefield’s Lakes Flying Company).

Aviation in Manchester began in 1784 when an adventurer called James Sadler took off from Long Millgate in the city centre in a hot air balloon, in front of 5,000 people who had each paid five shillings to see the amazing feat.

Even in 1908, five years after the Wright brothers’ flight, The Manchester Guardian said “We cannot understand to what practical use a flying machine can be put”, but others in the city had different ideas. In particular Alliot Vedon Roe. He wrote to the editor of The Times in 1905 predicting that a flying machine would be seen in England within a year. The Times echoed The Manchester Guardian in saying that all attempts at “artifical aviation” were doomed to failure, and added that in particular it would never be of any use in warfare. Roe did not agree. His timescale was wrong, but in 1907 he won £75 from the rather more forward-thinking Daily Mail for a large model aircraft he had built. In 1908 the first flight was made in Britain.

Despite the Manchester Guardian, by 1916 civilians in Manchester were being killed by bombs dropped from German airships. Thirteen people were killed in Kirk Street in Bolton by bombs dropped from a Zeppelin in September 1916 (though it was shot down by fighters of the Royal Flying Corps before it could get home).

Early on in the First World War Crossley began supplying engines for some of the first Royal Flying Corps planes, and in 1917 Crossley was asked by the War Office to create the second of three National Aircraft Factories.

The huge Crossley factory just outside Stockport

The huge Crossley factory just outside Stockport

Work on the factory began in October 17, and within nine months it had become what Lord Weir of The Air Council called “the finest of its class in the world”. The factory was in Heaton Chapel, just outside Stockport. This was land already owned by Crossley; work had begun in 1915 on an additional vehicle-making plant covering forty eight acres in all; the western side was used for aircraft manufacture. Two thousand five hundred people worked at National Aircraft Factory No. 2, turning out three hundred aircraft a month.

More land in High Lane, Heaton Chapel was requisitioned, and the total site covered fifteen acres. The first plane left the factory on March 16 1918 (a De Havilland DH9, registered D1001). Crossley moved into other locations too; workers were trained at the nearby Belle Vue pleasure grounds, and components were manufactured in the park’s King’s Hall and at the skating rink!

Dated 1918 but probably taken earlier; Crossley’s ‘National Aircraft Factory’. Note the large number of women craftsmen.

Dated 1918 but probably taken earlier; Crossley’s ‘National Aircraft Factory’. Note the large number of women craftsmen.

Wood was the main material for the construction of fuselage and wings, so carpenters were in great demand.

Wood was the main material for the construction of fuselage and wings, so carpenters were in great demand.

Fuselages mounted on trestles, close to completion of the carpentry stage.

Fuselages mounted on trestles, close to completion of the carpentry stage.

Now with wheels, the fuselages were fitted with a single engine.

Now with wheels, the fuselages were fitted with a single engine.

A completed DH9 waiting to be rolled out of the factory.

A completed DH9 waiting to be rolled out of the factory.

These weren’t marked as Crossleys; they were de Havilland DH9 and DH10 bombers. The large – 42 foot 6 inch wingspan – two-man DH9 was powered by a BHP/Galloway Adriatic engine, which was supposed to make the plane the fastest thing in the air. It was not only a lot slower than it was supposed to be though, but also unreliable, and the losses of pilots and bomb-aimers in DH9s was high. In time the engines in DH9s were replaced by either American ‘Liberty’ L-12s engines or Siddeley Pumas. The DH10 was an even bigger – 65 foot 6 inch wingspan – twin-engined plane, with the engines mounted between the wings on either side of the fuselage. Again it did not meet its specification, being capable of only 90 mph instead of the ‘guaranteed’ 110 mph. Rolls-Royce engines were ordered, which finally brought the aircraft up to spec. Crossley made two hundred DH10s, about a quarter of the total, and a larger number of DH9s out of just over four thousand in total.

Kenneth’s father William was made a baronet in 1909, but he died two years later during an operation. Sir William was a great philanthropist and was regarded as a very enlightened employer. Between 1903 and 1905 he paid for the building of the Crossley Sanatorium for Consumptives near Frodsham, at a cost of £60,000, which accommodated one hundred patients in an enormous four storey building set in sixty six acres of grounds. With his death his eldest son became Sir Kenneth.

As the son of a very successful industrialist, Kenneth had been educated at Eton and MagdalenCollege, Oxford, and in adulthood, to use a modern idiom, he lived and breathed Crossley Motors, and was constantly looking for better manufacturing methods and improvements in the technology. He was greatly respected by his workers, who appreciated both his devotion to the business, and his understanding of engineering. As the war came to a close the one thing which would have been uppermost in his mind would have been in which direction to take the company when military production ceased.

One immediate problem was the huge numbers of Crossley vehicles which were returned to England after the Armistice (the RAF alone repatriated 23,000 vehicles after the war). They couldn’t be allowed to flood the domestic market as this would have crippled sales of new Crossleys. This problem was exacerbated by the fact that the War Office was very tardy is cancelling the contracts. They were demanding new 25/30s (which superseded the 20/25s) well into 1919, and as soon as they were delivered they were marked as ‘Surplus To Requirements; For Disposal’.

Sir Kenneth made sure that as many of his ex-military vehicles as possible came back to his works. By then he had taken over the nearby AVRO factory by buying 68.5% of the company, and hundreds of Crossleys were stock-piled there. They were refurbished at the AVRO site and sold individually to the public at discounted prices, and many remained in commercial service for decades. There were so many to be sold that Sir Kenneth was, frustratingly, unable to justify launching a new range of vehicles until 1922, though this did give his design development office time to come up which greatly advanced vehicles.

With peace restored across Europe Sir Kenneth was able to fully enjoy like at Combermere Abbey. He had four young children to dote on, and three of them – his son and two of his three daughters – would follow him into his new-found passion for flying.

Sir Kenneth Crossley was at the height of his powers by the early Twenties. He ran a large, successful and profitable manufacturing company, with his surname over the door. He had a beautiful wife, Florence – to whom he had been married for twenty one years – and four lovely children at home in Combermere Abbey. He was involved in many civic interests in the surrounding countryside, as well as enjoying his hunting and shooting – as befitted a country gentleman. With his first, new, post-war range of cars about to be launched he had security on the one hand but also entrepreneurial excitement on the other. Also, so far as business was concerned, there were early discussions about some very exciting collaborations.

During the First World War Sir Kenneth had been in negotiations with the American vehicle manufacturer Willys-Overland. The company had come into being in 1908 when John Willys bought the Overland Automotive division of the Standard Wheel Company. Willys initially enjoyed great success on its home turf, running second to Ford in sales. A joint operation in the UK was agreed, and Willys Overland Crossley was created in 1919 to make cars which were badged as Overlands. One part of Sir Kenneth’s thinking may have been to take up production capacity in the Heaton Chapel factory, once military aircraft production had creased.

A period magazine advert for a Willys Overland Crossley, made in the Crossley factory east of ManchesterThrough the early Twenties the factory made Overland commercial vehicles, as well as cars, but for whatever reason they were not a commercial success. John Willys sold his shares in 1929 and left the board, and although vehicles were produced as late as 1934, great commercial damage had been done. The Heaton Chapel factory was closed and sold off to Fairey Engineering.

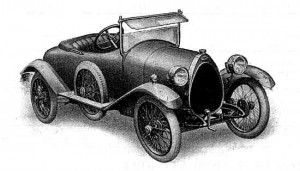

As that collaborative venture was dying, an even more audacious joint enterprise was being planned. Sir Kenneth went into business with Ettore Bugatti. This was another ambitious project, with a projected minimum production run of five hundred cars – thought in fact only twenty four were ever produced. The cars were assembled at the Crossley factory in Manchester from Bugatti components, and they were well received by motoring journalists. The 1924 range was made up of two, three, and four seaters, open or closed, and priced between £475 and £800; all very pretty cars, with the distinctive Bugatti horse collar-shaped radiator grille surround. It is hard to say why the Bugatti Crossleys were not successful, and together with Willys Overland Crossley they were rare set-backs for Sir Kenneth.

The very pretty Crossley Bugatti in two-seater form . . .

The very pretty Crossley Bugatti in two-seater form . . .

. . . and as a longer-wheelbase four-seater.

. . . and as a longer-wheelbase four-seater.

Before we get to World War Two it’s worth pausing over one other exercise, and it was only that – an exercise. This was the startling Crossley Burney Streamliner, of which only twenty five were made – all in 1934, and offered for sale for £750. Tear-drop streamlining was being tried by many car manufacturers, and one problem was that a large engine put a lot of bulk on the front of the car. The Crossley solution was to put the engine at the back; right at the back – the two-litre straight-six engine hung out of the rear, behind the rear axle. To achieve the streamlining the rear track was more than a foot narrower than at the front. Reviewers from ‘The Motor’ got it up to 78 mph at Brooklands and thought that it could have gone faster still. The bodywork, especially at the rear, was frankly hideous. Some do survive – there’s one in The National Motor Museum in Beaulieu. The cars which had failed to sell in 1934 at £750 were offered the following year for just £395.

The Streamliner was certainly ‘futuristc’ – but far from popular with car buyersAnother curious vehicle, this time with a quasi-military twist, had been built by Crossley in 1920. The previous year the government ordered the formation of the division of the Metropolitan Police, which became known in folklore as The Flying Squad. What was needed was an armed fast-reaction force which could operate all over Greater London, across the local police divisions.

The problem was one which the government did not want to admit to in the post-Armistice patriotic glow; the huge rise in criminal activity following the end of the war. The vast majority of returning soldiers were just pleased to get back to their civilian lives, to their wives and girlfriends, familiar surroundings, and jobs; others though saw Civvy Street in a different light. It wasn’t at all hard to smuggle firearms back into Britain, and having spent years killing Germans for King and Country, why shouldn’t they then do the same back home on their own account. Many of these ex-servicemen would have had criminal backgrounds anyway, but certainly others had been embittered by the war.

The first head of The Flying Squad was Detective Chief Inspector Wensley. He put together a team of a dozen detectives for Scotland Yard, and his team was called The Mobile Patrol Experiment. Its first vehicle was a horse-drawn cart. The officers hid in the canvas-covered back and peeped out through spy-holes. They weren’t much good for fast pursuit though, and it was decided that the squad should be given a fighting chance – and have the best vehicles available – so they were equipped with Crossley cars from 1920.

They also pioneered radio communications, and Crossley re-fitted an ex-military 20/25 tender for the squad for this purpose. To say it stuck out like a sore thumb would be an under-statement; the aerial mounted on top of it more than doubled its height. It had to be hidden in back streets away from the action, and certainly couldn’t be driven under low bridges. The idea that you could communicate with your officers while they were away from the police station was a revolutionary one, and gave The Flying Squad a distinct advantage over the baddies. The radio technology itself was ex-military too, needless to say.

The Crossley radio car supplied to The Flying Squad. Hardly a stealth vehicle.Crossley continued to make specialist military vehicles between the wars. During the First World War the British Army in India urgently needed an armoured car to cope with the very difficult terrain on the frontier. Both Rolls-Royce and Crossley were approached, and both made prototypes for evaluation. The Crossley not only performed better over rough ground than the Rolls-Royce product (sixteen of which had already been produced and delivered), but was less expensive. It was based on a chassis which Crossley had been developing for a lorry, and was taken for further evaluation by the War Office, now designated the IGL 1. Laden with four tons of dead weight it was driven for four thousand miles in the UK, and performed well. A total of thirty two more were ordered from Crossley, with armoured bodies to be made by Vickers.

An early Crossley armoured car, supplied to The War Office

An early Crossley armoured car, supplied to The War Office

A later model, now in The Tank Museum in Bovington

A later model, now in The Tank Museum in Bovington

The car rode on solid tyres as pneumatic ones did not last long in the heat, and to avoid punctures (on solid, disc wheels). The vehicle had a half-sphere rotating turret, and was fitted with one machine gun (which sat in one of four mounts), which was later increased to two. The first IGL 1 (known as IGA 1 in Crossley) was delivered in 1923, and in all four hundred and fifty were made. Two examples went to South Africa, and are both now in the national war museum. Others went to Japan, Argentina, and Estonia (the latter having bodies made in Sweden, with 7mm plate. The Japanese used their Crossleys – known as the ‘Dowa’ – in Manchuria and China in the early Thirties. Three Crossley six-wheel armoured cars were sent to Aden in 1930; all but one had the usual dome turret with twin Vickers machine guns, while one had a larger body and a tank-style turret with a single gun on top and another mounted by the driver.

Despite a weight of 4.8 tones the armoured cars could hit 37mph. The car had a crew of four, who sat in an asbestos-lined cab to keep the heat down. The body could be electrified to avoid attack from a mob.

In 1939 all the Crossley armoured cars in India were presented to the Indian Army. The bodies were retained, and mounted on Chevrolet rolling chassis (with twin rear wheels). In 1942 those that survived were passed to the Persian military. About twenty of the Indian Crossley armoured cars were used in anger in Palestine in ’41 and ’42.

Sir Kenneth Crossley signed another international collaboration contract in the early Twenties, to enter a War Office competition to produce a larger all-terrain vehicle. Crossley took their 15-20 cwt small lorry in rolling chassis form, and added Kegresse half tracks at the rear, supplied by Citroen-Kegresse.

The Kegresse system, developed by the French motor engineer Adolphe Kegresse in Russia between 1906 and 1916 to cope with Russian winters (and fitted to several cars owned by his principal employer, the Tsar), was deigned to be a simple bolt-on conversion – subject only to the modification of mudguards. This was a simple modification for Crossley to make during construction. The rear driving wheels were linked by a studded canvas or rubber belt.

The Crossley Kegresse

The Crossley Kegresse

Adolphe fled home to France as the Bolshevik Revolution unfolded in 1917, and sold the rights to Citroen in 1920. The military application of his system was obvious, and several motor manufacturers in different countries used it to build field ambulances, reconnaissance vehicles, staff cars and forward observation vehicles. Crossley made one hundred and fifteen, split almost equally between the 15-20 cwt and the larger three ton chassis. The three ton was a large open-backed truck, like a charabanc, used for troop carrying. Crossley used a belt across two wheels, both of which provided drive, with four smaller guide wheels in between. Production ran until 1929 and the vehicles more than proved their worth. A handful was sold for private use; probably for shooting parties on country estates.

Less successful was Crossley’s attempt at a prototype ‘Tankette’. Two were made; small, boxy and awkward-looking small tanks, designed to be used by one or two men. It had conventional front wheels, with Kegresse tracks close behind. The intention was to provide close support for artillery but it went no further.

Between 1919 and independence in 1922, Crossley 20/25 tenders were widely used in Ireland (alongside ex-WWI armoured cars. Archive photos show Crossley 20/25s in Dublin with slit sides, and chicken wire over a ridged frame to deflect stones and the like thrown by Fenian sympathisers. At the Michael Collins Centre at Clonakilty in West Cork a restored Crossley 20/25 tender is on display alongside a Rolls-Royce armoured car in a life-size tableaux showing the ambush in which Collins was killed. In 1922 four hundred tenders were transferred to the then-new Irish Army.

Through the late Twenties and into the Thirties Crossley moved slowly out of the private car market as competition increased, and concentrated on heavy good and passenger vehicles. Coach travel became very popular and Crossley met the demand for both buses and more luxurious coaches. In 1930 they offered the very first rolling chassis designed for a double-decker bus body. In 1933 they introduced their loyally-named ‘Mancunian’ single and double-decker buses, which proved to be one of the company’s mainstays for many years. Crossley’s lorries were known to be hard working and reliable, and thousands were made, for markets all round the world.

From the mid-Thirties onward Crossley manufactured large numbers of tenders for the RAF in anticipation of renewed hostilities against Germany, with seven hundred being produced. The company also met a new War Office brief for a four wheel drive three-ton lorry to replace the now-obsolete model. It had independent suspension, the 6.8-litre 38/110 engine used in Crossley buses, bolted to a five-speed ‘box. The War Office simplified the specification, opting for non-independent suspension and the older 5.2-litre 30/70 motor – and ordered 506 in truck form and 228 as tenders. Many of these were left on French soil before the Dunkirk evacuation, and the War Office then asked for another 700.

Crossley also supplied a few thousand four wheel drive tractors, often with trailers (known as Queen Marys), though with cabs made by a number of suppliers – including Park Royal, Mulliner, and English Electric, as well as Crossley themselves. These were made in a wide number of forms; crash tenders, ambulances, cranes, command vehicles, generator platforms, mobile wireless vehicles, and breakdown trucks. This family of four wheel drive vehicles was Crossley’s biggest ever production run; an average of 200 were built ever month. These ‘plain jane’ workhorses did sterling service and were a common sight in many theatres of war, and were ubiquitous on RAF sites.

After his early initiation into powered flight in 1913, Sir Kenneth’s passion for flying increased. He was very keen to build military aircraft again, and started talking to the War Office about fighter production in 1936. The government agreed to take over Crossley’s Stockport premises in 1938, and renamed it the Shadow Aircraft Factor Number 6, but then Fairey Aviation, who owned an adjoining site, successfully bid for the aircraft manufacturing contract – to Sir Kenneth’s great disappointment.

Sir Kenneth’s son and heir, Anthony Crossley was two years older than Fidelia. He was a well-regarded poet and author, who forged a career in politics. He was elected to Parliament in 1931 to represent Oldham, and in 1935 for Stretford. On the night of August 15 1939, little more than a fortnight before Britain’s declaration of war against his Germany, the small commercial aircraft he was travelling to Denmark in crashed into the North Sea in unexplained circumstances. Anthony had a son, Francis, who was ten at the time of his father’s death, who went on to join the Grenadier Guards, but he died of polio in 1953. Sir Kenneth had been robbed of his one grandson as well as his only son.

Anthony Crossley when a baby

Anthony Crossley when a baby

Anthony with his mother, Florence

Anthony with his mother, Florence

Anthony with his sister, Fidelia

Anthony with his sister, Fidelia

Anthony as a young man at Combermere; with hawk and young Irish Wolfhound

Anthony as a young man at Combermere; with hawk and young Irish Wolfhound

Sir Kenneth had daughters, yes, but no male heirs. He still delighted in being at Combermere Abbey, with his horses, his Irish Wolfhounds and his Staffordshire Bull Terriers. He used to tour the estate on a two-seat David Brown tractor, often accompanied by one of his children.

He also hunted big game, both in Africa and in the far west of Canada. A frequent companion on these trips was his good friend The Duke of Devonshire. He gave away many of his hunting trophies but there is still a number in the hall at the Abbey (which was shortened from the days when it was Viscount Combermere’s armoury). His African safaris always started with a cruise to South Africa on a ship of the Union Castle line, and in time he acquired a hunting lodge at White River, just to the west of the Kruger Park. He made this available to managers at Crossley, which must have been an enviable perk.

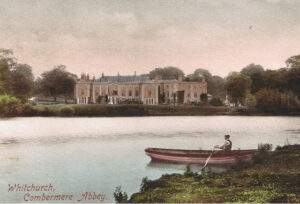

A picture postcard of ‘Combermere Abbey, Whitchurch’ dating from around the time Sir Kenneth bought the estate. This view was unchanged at the time of his death.

A picture postcard of ‘Combermere Abbey, Whitchurch’ dating from around the time Sir Kenneth bought the estate. This view was unchanged at the time of his death.

Production of Crossley cars had come to an end in 1938, and in 1945 the board agreed to look for a buyer for the rest of the motor company. It was bought by AEC, though they retained the Crossley badge until 1953. Sir Kenneth retired to Combermere, and lived quietly – no doubt able to look back on his commercial successes, but also reflect on his dynastic failure. He died in 1957, aged eighty, three years after his wife had passed away.