Edward Blore was born in Derby in 1787, the son of an antiquarian. He trained as an engraver and illustrator of antiquarian subjects – a profession he remained in until early middle age.

In 1826, in his fortieth year, having created impressive illustrations of a number of English cathedrals and great houses, he was appointed surveyor to Westminster Abbey, and the following year he was engaged to furnish plans for the chancel fittings of Peterborough Cathedral.

Blore’s fastidiously detailed work at Westminster Abbey was much praised. It was said of the draughtmanship; “This was his great forte. He had studied and drawn detail so long and zealously that its design came quite naturally to him, and in this respect he was incomparably superior to his contemporaries”.

He obviously gained a considerable reputation in this ecclesiastical line because soon afterwards he was employed to restore Lambeth Palace, then in a state of near ruin. His work there included an innovation – the construction of a fire-proof room for the preservation of manuscripts and archives.

Over the following few years Blore metamorphosed into an architect – without any training or portfolio – and in 1847 he was commissioned to re-model Buckingham Palace for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. He turned the C-shaped building in one with an enclosed central courtyard, much as we know it today (though King George V disliked it and had it further refined). At much the same time he enjoyed royal commissions to work on both Saint James’s Palace and Windsor Castle.

The entrance front of Buckingham Palace as designed by Edward Blore

The entrance front of Buckingham Palace as designed by Edward Blore

Edward Blore in late middle age

Edward Blore in late middle age

He was a close friend of the then-very fashionable author Sir Walter Scott, studied Scottish Baronial architecture with Scott, and went on to use it widely. Asked to design Prince Vorontsov’s massive palace at Alupka in the Crimea, he – schizophrenically – gave it a Scottish Baronial seawards façade, and a Moorish landwards face.

Above and below: The two contrasting facades of the palace Blore’s designed for Prince Vorontsov

Above and below: The two contrasting facades of the palace Blore’s designed for Prince Vorontsov

That Crimean commission was atypical of Blore’s work as the vast majority of his commissions were across the British Empire – including the wonderfully inappropriately gothic Government House in Sydney. He was very much an establishment and imperial figure. He died in 1879 at the great age of ninety two, and is buried in Highgate Cemetery – in a plain and disappointingly unadventurous tomb.

That Crimean commission was atypical of Blore’s work as the vast majority of his commissions were across the British Empire – including the wonderfully inappropriately gothic Government House in Sydney. He was very much an establishment and imperial figure. He died in 1879 at the great age of ninety two, and is buried in Highgate Cemetery – in a plain and disappointingly unadventurous tomb.

All of which raises the fascinating question of how – and why – Edward Blore came to design the stable block at Combermere Abbey. Surely he was far too grand, and probably far too expensive, for such a modest commission?

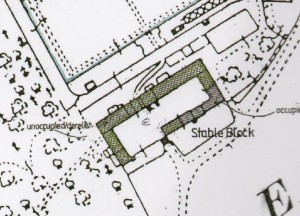

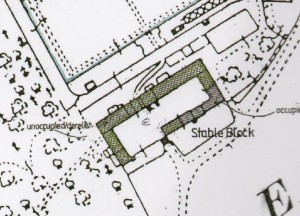

The stables (which are now Grade II listed) were built in 1837 on or close to the site of the original Abbey farm, or grange. The range is about a thousand feet from the house, which seems like an inconveniently long way, and on slightly higher ground. They were built of local brick with stone detailing, under a slate roof. The plan is a long rectangle, more than three times longer than wide, running north east to south west. They included a number of staff cottages within the overall structure, which accommodated carriages as well as horses – enclosing a large, open cobbled courtyard.

A plan of the stable block in Edwardian times. It shows an absence of any buildings to the south-east of the main gate; this is correct – there is a wall but no structures.

A plan of the stable block in Edwardian times. It shows an absence of any buildings to the south-east of the main gate; this is correct – there is a wall but no structures.

A clue might lie in the year. Also in 1837 Blore was engaged to work on Crewe Hall, the home of Hungerford Crewe, the third Baron Crewe – who was a historian and aesthete, and went on to be a very enthusiastic and active fellow of both The Society of Antiquaries and The Royal Society.

Baron Crewe was one of the largest landowners ion Cheshire, with estates totalling more than ten thousand acres and bringing in £37,000 a year. He commissioned Blore to make alterations and enlargements to Crewe Hall, which was built between 1615 and 1634, at a total cost over five years of £30,000 – close to a year’s income for the Crewe estate (by way of comparison, in 1852 Victoria and Albert bought Balmoral Castle and fifty thousand acres for £32,000).

Baron Crewe’s brief to Blore was to make all the interiors more sympathetic to the external style of the original Jacobean house – most noticeably replacing the screens passage with an entrance hall, and covering over the central courtyard to create a single-storey hall. Blore also created a number of modernisations – including the installation of an innovative warm-air heating system.

Most interestingly for us, Blore added a centrepiece and a clock tower to the stables quadrangle and built a gate lodge. The original stables were very handsome. Built in red brick with a tiled roof, they were completed around 1636, and were contemporaneous with the house. The stable block was situated close to the house’s entrance front and at a right angle to it. It had, and still has, nine bays with an attic floor above.

Blore’s new centre-piece was a stone archway in the middle of the block, flanked by pilasters, with an ornamental stone balcony above, topped off by a tall brick and stone clock tower pierced by arrow slit windows, with a stone ogee cupola on top. To this day this confection looks like a slightly awkward addition.

Blore’s new entrance and clock tower at Crewe Hall – hardly any distance from Combermere Abbey, and owned by an ex-soldier who Viscount Combermere doubtless knew well

Blore’s new entrance and clock tower at Crewe Hall – hardly any distance from Combermere Abbey, and owned by an ex-soldier who Viscount Combermere doubtless knew well

Although everything else at Combermere Abbey was gothic by this period, the stable block which Edward Blore designed was neo-Jacobean, and not unlike the one at Crewe Hall – though less elaborate. It would not be at all surprising if Blore met Viscount Combermere while the former was at Crewe Hall – each would have known the other by reputation, in their different fields – and Combermere had asked the architect to build him a new stable block. It may have been socially embarrassing for Blore to refuse the request, and he may well have known that the fee could be earned easily and quickly.

One would have expected the block to be designed in the gothic style in concert with everything else at Combermere, but perhaps the Viscount failed to specify this, and perhaps Blore – or one of his assistants – rather dashed off a plan and elevations based on what was being worked on a dozen or so miles away at Crewe.

There would have been stables in use at the Abbey, in some form or other, for working horses across more than eight hundred years – from the creation of the Cistercian monastery at Combermere in 1133, right up to the post-War years in the middle of the Nineteenth century.

We know nothing about the use of horses at the Abbey before the Dissolution, though we do know that in 1309, during the reign of Edward II, one Richard of Fullshurst lead a band of aggrieved locals – who were probably owed money by the constantly-indebted Abbey – in a raid on the house, when goods to the value of £60 were stolen and three of the Abbey horses were killed.

After the Dissolution, when the wealthy and influential Cotton family were in possession of the estate, there would have been many horses in the stables (as well as hard-working horses stabled at the Abbey farm). Horses were vital for personal transport (for anyone of any wealth) as well as for senior servants out and about on Abbey business. In the Tilleman’s panoramic painting of the estate, created in the early Eighteenth century, we see a number of people on horse-back, mostly in two groups; one, including the then-master of the house, returning to the Abbey by what was then the main entrance, and a second, including a lady riding side-saddle, hunting deer.

From the Tillemans painting of the Abbey; above, horsemen approaching the house, and below, a hunting party on horse-back in pursuit of deer in the park

From the Tillemans painting of the Abbey; above, horsemen approaching the house, and below, a hunting party on horse-back in pursuit of deer in the park

What may well have been the stables at that point are shown to the east of the house; a simple, timber-framed structure. A country house of this size would also have had tack stores, storage for fodder for the horses, and probably its own smith or metalworker, who had duties as a farrier.

What may well have been the stables at that point are shown to the east of the house; a simple, timber-framed structure. A country house of this size would also have had tack stores, storage for fodder for the horses, and probably its own smith or metalworker, who had duties as a farrier.

The many men of the Cotton family who had military careers would have been expert horsemen, including of course the first Viscount Combermere, who made his name as a cavalry officer.

As early as 1859 the Abbey’s owner, the second Viscount Combermere, was offering his horses for sale, and in 1871 and 1882 further extensive sales of thoroughbreds and hunters were held. More on this can be read by clicking here.

Sales particulars for the sale of horses from the second Viscount Combermere’s stables

In the late Nineteenth century the estate was leased to Elisabeth, Empress of Austria for two hunting seasons. We know that there were around three dozen horses which could be used for hunting in the Abbey stables (or elsewhere on the estate) at that point, but she augmented that number by bringing some of her own favourite hunters.

Above and below; photographs of Elisabeth, Empress of Austria sitting side-saddle on a hunter

Above and below; photographs of Elisabeth, Empress of Austria sitting side-saddle on a hunter

Despite the coming of the motor car there were horses at Combermere throughout the first half of the Twentieth century, many kept for hunting. After the death of Sir Kenneth Crossley in 1957 a small number of horses and ponies were kept in the stables for recreational use. A shed was built in the stable block to house tractors, and the carriage houses were used as garages for cars. The block boasted its own petrol pump for fuelling these cars. The original cobbled surface in the yard was concreted over, but fortunately it was possible to remove that and reveal the cobbles (complete with their drainage channels).

Despite the coming of the motor car there were horses at Combermere throughout the first half of the Twentieth century, many kept for hunting. After the death of Sir Kenneth Crossley in 1957 a small number of horses and ponies were kept in the stables for recreational use. A shed was built in the stable block to house tractors, and the carriage houses were used as garages for cars. The block boasted its own petrol pump for fuelling these cars. The original cobbled surface in the yard was concreted over, but fortunately it was possible to remove that and reveal the cobbles (complete with their drainage channels).

The stable block always included accommodation for staff, and they would have been very pleasant homes – fairly large, attractive, and, being south-east facing, very light.

In 1992, soon after Sir Kenneth Crossley’s great-granddaughter Sarah Callander Beckett took on the estate, it was decided to convert the block into a total of nine holiday cottages for short-term lets, sleeping, in all, up to forty nine people. By then the buildings were in a poor state of repair and mostly redundant, and this was to give the whole block a very worthwhile new lease of life – as well as providing a new source of revenue for the estate.

The stable block during restoration and conversion into luxurious holiday cottages

Prior to this date one cottage was still occupied, one had been vacated in the mid-Seventies, and one had been used by a tenant as a fish smokery for a while. Conversion work began in 1993, with the majority of the work being undertaken by a local building firm, Galliers and Son of Shrewsbury. They architects were Arrol and Snell, also from Shrewsbury, who have been associated with the Abbey for many years, and John Pidgeon of Shifnal in Shropshire was the quantity surveyors on the project. The conversion was completed the following year, each cottage was individually decorated, and a marketing operation was embarked upon immediately. The cottages are now very highly regarded and very popular. An upmarket wedding venue has now been created in the restored gardens behind the stable block, and the cottages are often taken en bloc by friends and family of the bride and groom.

The conversion of the block has won awards from the Country Landowners Association and the Rural Development Programme for England. The cottages themselves have won awards from Visit England, Green Tourism, Enjoy England, the Hudson Heritage Awards, and Marketing Cheshire – as well as the Visit England Gold award for self-catering, thus numbering the cottages among the very best in the England . They have frequently been the recipients of lavish praise in press reviews, both in print and online.

Above and below; awards for the conversion of the stable block from national organisations

Above and below; awards for the conversion of the stable block from national organisations

The block from the park after restoration, looking from the south-east

The block from the park after restoration, looking from the south-east

The rear of the stable block, facing the southern end of The Walled Garden, looking to the south-east

The rear of the stable block, facing the southern end of The Walled Garden, looking to the south-east

Above and below; the cottage at the south-west corner of the block, seen from the park. The entrance arch is to the right

Above and below; the cottage at the south-west corner of the block, seen from the park. The entrance arch is to the right

The south-east corner of the main facade of the block, asymmetrical from the south-west corner

The south-east corner of the main facade of the block, asymmetrical from the south-west corner

The north-eastern face of the block, from what is now the guests’ car park

The north-eastern face of the block, from what is now the guests’ car park

Inside the stable courtyard, looking to the north-west

Inside the stable courtyard, looking to the north-west

The north-west corner of the courtyard

The north-west corner of the courtyard

The carriages houses in the north-west range of the stable block

The south-west face

The south-west face

Above and below; cottage interiors after conversion